Paper Conservation Pitfalls

by Susan Duhl

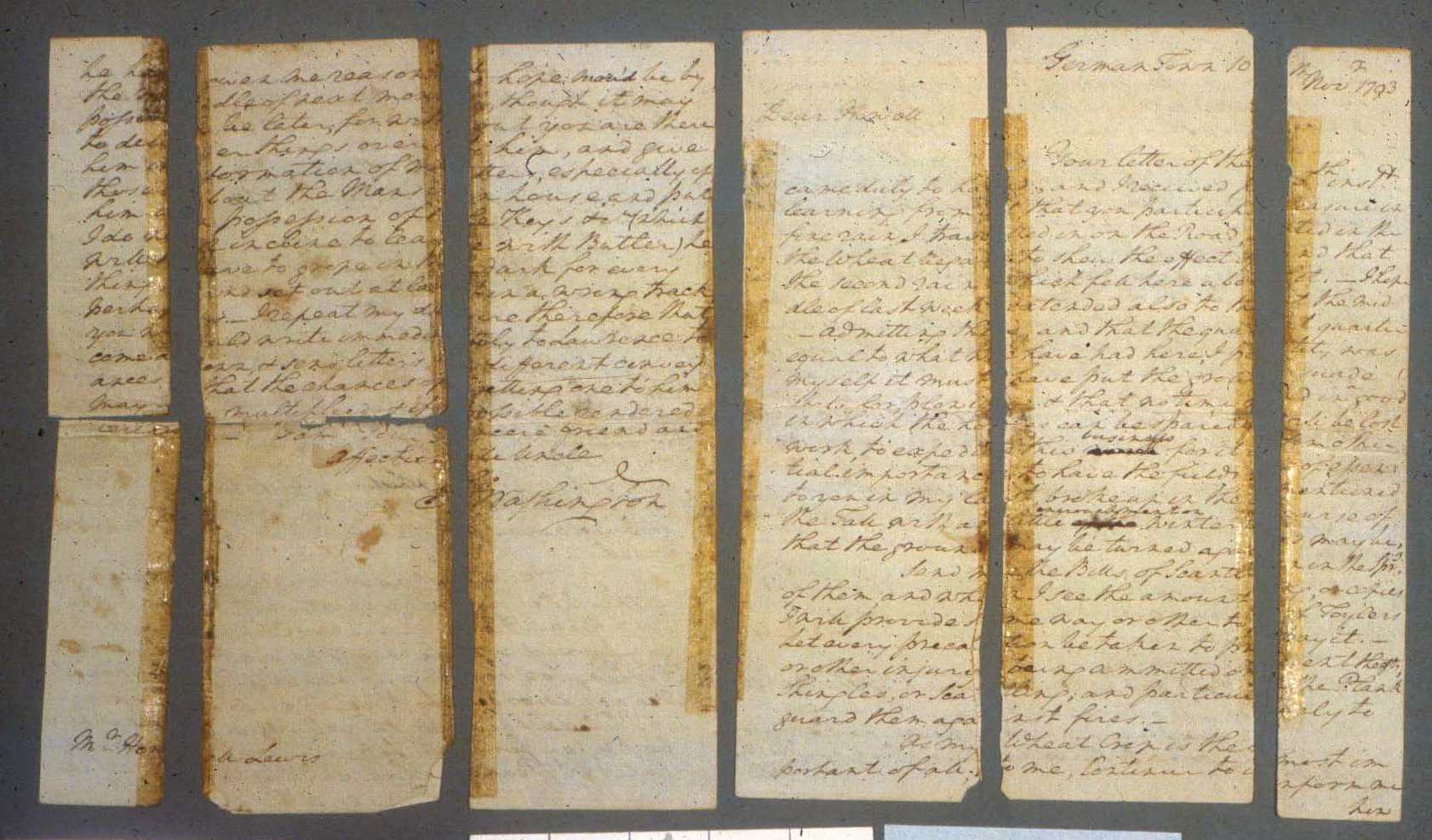

It is remarkable the things people think of to 'fix' paper, only to make them worse: pastels washed off in the bathtub, painted surfaces rubbed with glass cleaner, and images ripped off when removing window mats. My colleague once shrugged and joked: "It's what keeps us employed!" My own aggravation is the do-it-yourself advice on the Internet - including cleaning paper using bread. That won't work. Commercial breads have many ingredients, including oils that stain and salt that is abrasive.  | | Tape Mends |

You will find many resources on the Internet that show how to undertake treatments. While it might be tempting, remember that there are contingencies, potential problems, and professional liabilities in undertaking treatments on paper collections without hands-on training provided by a conservator. Some common examples of bad outcomes for do-it-yourself paper treatments include: spray applications of 'de-acidification' solutions, which can easily dissolve media and discolor paper; poor quality erasers and erasing techniques that either abrade paper surfaces or leave a harmful residue; or humidification and flattening, which can alter media or create physical stress resulting in tears, or other damage. Proper housing and handling is the greatest contribution a collections manager can make to the preservation of paper-based collections. Treatments are a second step that should only be undertaken after hands-on training with a conservator. Training helps you understand what you can do yourself and when you need to call a conservator. Conservators schooled in the United States are trained in art history, studio art, and organic chemistry in order to understand: - how art and artifacts are manufactured;

- how art and artifacts age and deteriorate as a function of their composition;

- the interaction of pieces with the environment to which they are exposed;

- and the use and handling of art and artifacts in research and exhibition.

Learning how to work with conservators, and about the services they offer, can be a great help to you. Understand the concepts behind safe and ethical treatments. Be familiar with conservation and preservation terminology. And understand conservation contracts and why certain treatments are proposed or not. Additionally, understand the costs associated with preservation supplies and conservation treatments. Much of this comes from experience. Start by reading the American Institute for Conservation's "Working with a Conservator."Paper can last indefinitely with proper care and maintenance.

Excerpt from MS228: Care of Paper Artifacts taught by Susan Duhl.

Susan Duhl is an Art Conservator in private practice specializing in art on paper and archival collections. Susan completed her Master of Art degree and Certificate of Advanced Study in Art Conservation from the State University College at Buffalo Art Conservation Program. She is a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC) and founding member of the Art Conservators Alliance.

|

|

Collection Labeling Kit

Based on work by the AIC/AAM Joint Committee on Numbering, this kit provides three ½ ounce brush top bottles of different clear lacquers, two bottles of solvents, and bottles of black and white acrylic inks. Included are three different ink applicators: a fine brush, a quill pen and an empty COPIC marker. Three different pencils, two that are water soluble, samples of different tags and ties, and gloves also are included. A small booklet provides information on how to use each of the items in the kit.

How an item is labeled depends on what material makes up that object. Northern States Conservation Center teaches a course on how to decide what materials to use on your collection -

Labeling Kit Price: $ 77.55

|

Regional Workshops

Where you can find some of our instructors this year:

Peggy Schaller

Security for the Small Museum: Practical Low and No Cost Solutions. $20 cost. - September 17. 2012, 10am to 3 pm: Animas Museum, 3065 w 2nd Ave, Durango, CO

- September 19, 2012, 1 pm to 5 pm: Wyoming State Museum, 2301 Central Ave., Cheyenne, WY

- September 25, 2012, 1 pm to 5 pm: Denver Museum of Miniatures, Dolls and Toys, 1880 Gaylord St., Denver, CO

- September 28, 2012, 8 am to 12 pm: Golden History Center, 923 10th Street, Golden, CO

For more information: Peggy Schaller

Toll free 1-877-757-7962

information@museumcollectionmgmt.com

Gawain Weaver

Photograph Care and Identification Workshops

- July 30-Aug 3: Los Angeles, CA

- August 21-24: Wash, DC

- September 17-20: Philadelphia, PA

- October 15-18: Atlanta, GA

Introduction to the History and Technology of Photographic Materials |

|

|

Welcome to the Collections Caretaker e-Newsletter from Northern States Conservation Center. The newsletter is designed to bring you timely and helpful content that is pertinent to situations we all encounter in our museum and archives work. Feel free to let us know what topics you would like to see featured in Collections Caretaker or even contribute an article.

|

|

Moving and Handling Furniture

by Craig Deller

Generally speaking, the best way to handle furniture is to leave it alone. Antique chairs, dressers and the like should be handled as infrequently and gently as possible. When you must handle furnishings, it's important to protect the object from your hands by wearing gloves. While many museum professionals recommend cotton gloves, I advise against this practice. Cotton provides a poor grip on the often smooth surface of finished wood. Instead, try nitrile surgical gloves, which provide better grip and excellent protection to you and the furniture. Because moving furniture increases the risk of damage (to the movers and the moved), it should only be tried when absolutely necessary and after careful preparation and planning. Remember that moving any museum object from one location to another can create environmental stresses by changing environmental conditions such as relative humidity, temperature and light levels within a short period of time. When planning a move, consider the safety of both staff and the object. Have enough people on hand to comfortably lift, steer and guide the object without subjecting any person to the risk of physical injury or strain. Personal safety is directly related to the object's safety; somebody barely able to control a heavy object is more likely to drop it or knock it against other objects, doorframes and the like. An accurate assessment of the object's weight and bulk is crucial. Most furniture requires at least two people to move it safely. It's also important to have people on hand to guide the staff doing the heavy lifting and to keep their path clear. Clarify everyone's role in advance. Lift the item straight upwards, applying force to the lowest load bearing member, and coordinate the efforts of all those bearing the weight. All legs or supports should share the load to prevent excessive stress on joints. Avoid tipping or dragging and be prepared to construct temporary supports for unwieldy components or objects. Before moving anything, assess the surfaces that will be touched during the move. If they are vulnerable - water-gilded surfaces, for instance - they must be protected from handling and abrasion. Remove anything that will slide off or that could become detached during the move. Marble and glass tops and mirrors should be carried vertically because they can break under their own weight. To lift a marble top first nudge it forward, then tip it on to its back edge, supporting the underside. At its destination, set it down vertically on pre-arranged supports. Remove loose drawers and other intentionally removable items, but consult - and heed - a specialist before unscrewing components or undertaking similar levels of dismantling. Ensure that separated items such as multiple drawers are clearly marked so they can be returned to their former positions. Lock any doors and drawers that will stay in place during the move. Excerpt from MS226: Care of Furniture and Wood Artifacts. MS226: Care of Furniture and Wood Artifacts is taught by Diana Komejan. She graduated from Sir Sandford Fleming Colleges Art Conservation Techniques program in 1980. She has worked for Parks Canada; Kelsey Museum, University of Michigan; Heritage Branch Yukon Territorial Government; National Gallery of Canada; Canadian Museum of Nature; Yukon Archives and the Antarctic Heritage Trust and is currently teaching Conservation Techniques in the Applied Museum Studies Program at Algonquin College in Ottawa. In 1995 Ms. Komejan was accredited in Mixed Collections with The Canadian Association of Professional Conservators. Her work as a conservator has been quite broad in scope, having worked with historic sites, archaeological excavations and museums |

|

Developing a New Exhibition

by Lin Nelson-Mayson

Start with the mission

All museum activities should begin with the museum's mission statement, including exhibitions. When a museum evaluates the relative merit of exhibition and program ideas, the mission is the guiding point for decision-making and resource allocation.

Exhibitions are the museum's main communication vehicle and certainly one that utilizes a large amount of a museum's resources. Starting with the mission enables the museum staff to ground ideas in a solid relationship with the institution and develop clarity of communication about the exhibition message.

The Big Idea

Although objects are the central focus of a museum collection, an idea or message is generally the starting point for an exhibition. In fact, many exhibition proposals or scripts begin with the central theme or, as Beverly Sorrel terms it, the Big Idea. The Big Idea is the essence of the exhibition, the take-away message, as it were. An object, such as a teapot or chair, can be the source of this message, or it can be a concept, such as innovation or racism. In evaluating ideas for potential exhibitions, articulating the Big Idea can be a valuable exercise in clarifying the idea. An inexpensive evaluation technique is to ask a visitor to state his or her perception of the exhibition's Big Idea. It may not be the one intended by the exhibition team! Like a museum's mission statement, the clear central message, or Big Idea, helps those working on the exhibition make appropriate choices that convey the message and helps to focus the exhibition components to achieve it.

While a museum's collections support its mission and can form the backbone of the visitors' experience, temporary exhibitions can support these collections by offering a larger range of objects and subjects than may be contained in the collections. Temporary exhibitions can reflect new achievements or developments in areas of interest to the museum, they may include objects that are too large or too expensive for

the collections, and they may explore subjects that are related, but not central to the museum's mission. While long-term exhibitions form the core message and experience presented by the museum, temporary exhibitions support this message with a fresh look and can attract new visitors to the museum based on an expanded subject or time sensitive viewing opportunity.

Support strategic plan

Fundamentally, all exhibitions are developed as part of a comprehensive planning process that includes educational goals, financial planning, community outreach and partnership, and collections stewardship.This planning process provides the framework for decision-making about exhibitions and their importance to the museum. Who are the audiences we are trying to reach? What resources do we have to achieve our goals? A regularly reviewed strategic plan can assist museum staff in forming a philosophical basis for exhibitions, in selecting exhibitions for development, and in determining what exhibitions to change.

Know your audience

The Big Idea is of no use if it is aimed at the wrong audience. Audiences for exhibitions can be estimated based on your current audience, the audience for similar exhibitions, and new audiences to whom press materials are targeted. Identifying the audience for which the exhibition is aimed enables the exhibition team to set a tone for text development, make decisions regarding physical questions for gallery construction (wheelchair access? Child-friendly seating?) And choices regarding text production (larger text size for aging eyes? light on text panels in a gallery darkened for conservation purposes?).

Finding ideas for exhibitions

Brainstorming for exhibition ideas is a fun way to spend a staff retreat. The collections, community activities, funders' suggestions, anniversaries of events, and new discoveries can be sources for exhibition topics. Exhibitions can be collaborative projects with other community agencies or with museums that agree to co-develop an exhibition that will open at one site and travel to the next. Although this is a complex project, it often allows the partner museums to develop a more complex exhibition than either is capable of mounting on their own. Traveling exhibition organizers are great sources for exhibitions that come in a wide range of subjects, sizes and prices.

Excerpt from MS 106:Exhibit Fundamentals: Ideas to Installation.

Lin Nelson-Mayson teaches the new course, MS244: Traveling Exhibitions as well as our core exhibit course MS106: Exhibit Fundamentals: Ideas to Installation. With over 25 years of museum experience at small and large institutions, Ms. Nelson-Mayson is director of the University of Minnesota's Goldstein Museum of Design. Prior to that, she was the director of ExhibitsUSA, a nonprofit exhibition touring organization that annually tours over 30 art and humanities exhibitions across the country. For five years, she was a coordinator or judge for the American Association of Museums' Excellence in Exhibitions Competition. She currently serves on the exhibition committee for the National Sculpture Society. Ms. Nelson-Mayson has extensive experience with the planning, preparation, research and installation of exhibitions. Ms Nelson-Mayson's experience includes teaching museum studies and museology courses. Her particular interest is the needs of small museums.

|

|

What is a Museum?

by John E. Simmons and Kiersten Latham

While many definitions of 'museum' exist, there is no real consensus about what makes a museum. When Burcaw (1997) wrote his chapter on museum definitions, the questioning of the existence, character, and value of museums was already well under way, and the discussion continues today. The reason for this is really quite simple - museums are dynamic institutions that respond to changes in social trends, beliefs, and cultural expression. In trying to define what a museum is we can examine core functions as a starting place.

It is important to remember that how museums are defined is not merely an academic question, because how you define a museum impacts on an institution's ability to obtain funding, its legal status, its tax status - all sorts of things.

The word museum comes from the Greek word mouseion, meaning the place where the Muses dwell, a reference to the Temple of the Muses, a place where objects and learning were associated (the Muses were the sister-goddesses of mythology). The Greek word muse is derived from a word that means "to explain the mysteries," which is really what museums are all about - explaining the mysteries of life to the visitors.

Legally, the courts have long considered a museum to be "a repository or collection," and most people would say that museums are institutions that have collections, exhibit their collections, and hold the collections in a public trust.

Typically, we tend to think of museums as fitting into categories such as history, art, natural history or science, or general museums. However, the contents of the museum seem not to be an issue with respect to the museum definitions in the literature. There are obvious types of museums that we would not even question, such as the art museum or the natural history museum. But sometimes the kinds of things found in a museum are not so obvious. Consider, for instance, the European Asparagus Museum in Germany, or the Woodturners Museum in Minnesota. What kind of museums are these?

Debates and Disagreements

Debates about what makes a museum seem to swirl around two primary considerations: the presence (or absence) of collections and the museum's role as a public institution (and the type of responsibility that ensues).

Many institutions that do not keep collections but exhibit collections claim they are still museums because of the interpretive, educational and public nature of their programs. This leads to an important, fundamental question - must an institution own objects in order to be a museum? Consider, for example, science centers. Science centers are usually based on hands-on activities designed to instruct visitors about the natural world (the physical universe). Often the only 'collections' that science centers hold are the exhibits (temporary) that are used by visitors, built for the specific purpose of teaching various science concepts. These objects in science centers are not preserved, nor are they representative of some time, culture or species, but rather they are absorbed into the idea behind the museum. Other types of institutions have objects that some would not call collections or would find difficult to call objects. Zoos, for example, hold collections of animals. Are zoos a type of museum? Zoos collect, systematically care for their collection, educate the public about them (interpret the collections), and are open regularly to the public. Does this fit with standard museum definitions? What about libraries? Are books objects? Aren't they publicly accessible and available for educational purposes? Should online access to collections count as public accessibility?

Social Responsibility?

A perennial issue of late has been the question of what role museums should play in society. Should museums be passive holders of knowledge that store, preserve and display objects and give basic information to the public about these objects? Or, should museums take an active role in bringing issues, sometimes controversial, to the forefront? Should museums be catalysts for asking questions, building and inspiring new knowledge, and stimulating dialogue? Although we in the US are accustomed to most museums presenting information in what seems to be a neutral voice, in other parts of the world museums take on very different roles in addressing issues of race, equality, and history. Could (or should) a museum about slavery or the history of Native Americans be neutral in its presentation of information?

Virtual Museums

Much debate and discussion currently surrounds the idea of the virtual museum. This is not a simple issue. What is considered 'virtual' actually falls on a continuum from a collection of digitized objects online to an actual immersion experience using high-tech equipment to make one feel as if they are in a museum. Many museums are using "Second Life" technologies, taking advantage of new paths to untapped audiences. Some people worry that the virtual version will someday replace the physical version of the museum. Other people contend that this can never happen, that the physical museum - its building, objects, people, and exhibits - will always be important to society. Younger generations are growing up in virtual and digital worlds, seeing as normal what many of their elders find jarring and new. What role might new technologies play in the debate about physical collections vs. public access? Technology allows greater access to museums and their collections, but without the experience of actually seeing the real objects. Virtual access is cheaper and perhaps easier (or at least quicker) than building and accessing physical exhibits. On the other hand, physical collections provide an experience that is radically different from a virtual experience. Several studies cite the importance of seeing the 'real' thing and being in the presence of a complete exhibit, surrounded by artifacts, design, lights, colors, sounds, etc. The jury is still out on this issue, but it is an important one for anyone entering the museum field to think through carefully and thoughtfully.

Summary

Consider this idea from Susan Pearce: "The point of collections and museums...revolves around the possession of 'real things' and... essentially this is what gives museums their unique role."

Excerpt from MS101: Introduction to Museums.

John E. Simmons runs Museologica, an independent consulting company, and serves as Adjunct Curator of Collections at the Earth and Mineral Sciences Museum and Art Gallery at Pennsylvania State University. He has a B.S. in Systematics and Ecology and a Master's degree in Historical Administration and Museum Studies. Simmons began his professional career as a zoo keeper, then worked as collections manager at the California Academy of Sciences and the Natural History Museum of the University of Kansas, where he also served as Director of the Museum Studies Program until 2007. In 2011, he received the Carolyn L. Rose Award for outstanding commitment to Natural History Collections Care and Management from the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections. He is a recipient of both the Superior Voluntary Service Award from the American Association of Museums and the Chancellor's Award for Outstanding Mentoring of Graduate Students from the University of Kansas. Simmons' publications include three books, Herpetological Collecting and Collections Management (2002), Cuidado, Manejo y Conservación de las Colecciones Biológicas (2005, with Yaneth Muñoz-Saba), and Things Great and Small: Collections Management Policies (2006). He consults, teaches, and does field work in the US, Latin America and Asia.

|

Northern States Conservation Center (NSCC) provides training, collection care, preservation and conservation treatment services. NSCC offers online museum studies classes at www.museumclasses.org in Collections Management & Care, Museum Administration & Management, Exhibit Practices and Museum Facilities Management.

Sincerely,

Helen Alten, DirectorBrad Bredehoft, Sales and Technology Manager

|

|

|

|

|

|

|