Government Grants vs. Private Foundations

by Helen Alten

How do government grants differ from private grants? Foundations rarely use standardized application forms. In fact, some foundations prefer a brief letter of inquiry before submitting a proposal. Some foundations share a common grant application form. Government grants always have a standardized form or format.

Reviewers for government grants, especially federal grants, are probably experts in the field of museums and preservation. Foundation reviewers are usually generalists. Funding cycles for government grants can take as long as a year between application submittal and receipt of funds. Some foundations fund quarterly and funds can be received quickly once the application is approved. Government grants tend to be specific while foundations use much broader funding categories. Any funded U.S. Government grant comes under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) - which means you can receive a complete copy, except for salary information, of any previously funded grant. FOIA does not apply to private foundations.

Common to All Funders

All funders require well-written proposals. Use active, not passive voice. Avoid jargon and acronyms. Have a friend from another career read your grant proposal and circle any words they don't understand. Keep sentences simple and paragraphs short. Hire an editor. Use headings and subheadings. Be accurate. Make no mistakes. Double and triple check all facts and figures. Do your homework. Get price quotes. Respect deadlines. Do not fax or e-mail without prior permission. Do not use boilerplate text.

Most grants are now submitted using electronic forms. This makes it easier to make mistakes. Be sure to print off and check the text before pressing that "send" button. Because computers fail, make sure to send the grant days before the deadline. Then call to make sure they received it. Don't wait until the last minute. Sometimes the system crashes because everyone is submitting at the same time. So beat the rush and make sure to get it in.

Excerpt from MS302: Fundraising for Collections Care.

Helen Alten is the founder of Northern States Conservation Center and an objects conservator with 30 years experience. She has been working with small museums throughout the US for over 20 years. Helen teaches many courses for museumclasses.org including MS 213: Museum Artifacts: How they were made and how they deteriorate, MS243: Making Museum Quality Mannequins, and MS302: Fundraising for Collections Care.

|

Scholarship Opportunity

Beginning in January 2012 the Iowa Conservation and Preservation Consortium (ICPC) will be offering a reimbursement scholarship to Northern States Conservation Center's online classes. The scholarship for ICPC members is available to Iowa residents working in a Museum, Historical Society, Library, Archive, Genealogical Society Library, Government Record Office or other institution that preserves the history of Iowa. We will post a link to the scholarship application when it becomes available. Want a scholarship but are not a member of ICPC? Other museum service organizations could provide similar services. We would be happy to work with your regional organization to make this happen. |

Regional Workshops

Where you can find some of our instructors this year:

Ernest Conrad

NYC Building Codes

- Jan. 27: White Plains, NY

Sarah Brophy

"I'm on Overload! There's No Time for Environmental Sustainability!"

Small Museum Association Meeting Keynote Speaker

Helen Alten

Collections Management and Practice, AASLH Workshop

- June 13-14: New Orleans, LA

Gawain Weaver

Photograph Care and Identification Workshops

- Feb 21-24: Los Angeles, CA

- Mar 26-29: New York, NY

- Apr 23-26: Can Francisco, CA

- Jul 16-19: Austin, TX

- Sep 17-20: Philadelphia, PA

- Oct 15-18: Atlanta, GA

Peggy Schaller Security for the Small Museum: Practical Low and No Cost Solutions - January 23, 2012: Frisco, CO

Collections Management Boot Camp - May 14-18 2012: Estes Park, CO

Lin Nelson-Mayson "Making the Transition from Student to EMP" Career Cafe Session - At the American Association of Museums Conference in Minneapolis, April 29 to May 2

|

|

|

Welcome to the Collections Caretaker e-Newsletter from Northern States Conservation Center. The newsletter is designed to bring you timely and helpful content that is pertinent to situations we all encounter in our museum and archives work. Feel free to let us know what topics you would like to see featured in Collections Caretaker or even contribute an article.

|

|

Board and Staff: Welcoming the Green Revolution in Your Museum

by Sarah Brophy

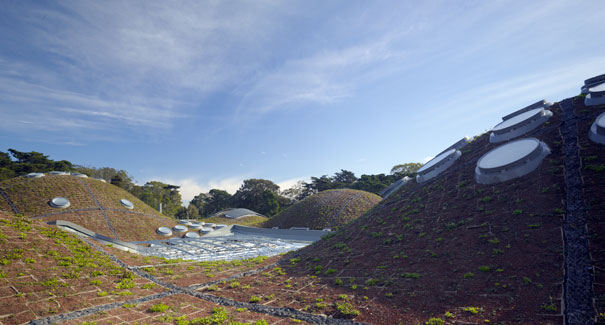

"Our board," says Patrick Kociolek, executive director and curator of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, "has never balked at LEED - or even Platinum-certified." In fact, they have a "huge commitment to green." That commitment, Kociolek notes, came after the academy's board, staff, and stakeholders in the community engaged in a thorough planning process that led to the decision to create an institution for the 21st century.

| | Sustainable Design at the California Academy of Sciences |

Because museum boards are designed to be representative of the communities they serve, the chances of your board being "true-blue green" from the outset are relatively slim. The lawyers, financiers, corporate leaders, accountants, and others who sit on most museum boards don't start out green; they become green. The same holds true for staff.

How do they become green? Julie Silverman, Director of New (that's her title) at ECHO at the Leahy Center for Lake Champlain in Burlington, Vermont, stresses the importance of the individual's "willingness to learn new ways and to change behavior." The board and staff of ECHO saw the need for a new building before they were fully committed to sustainable design; once they made the commitment, however, the rest was easy. In a state like Vermont, one of the "greenest" in the country, selling the benefits of sustainability to boards and staff usually isn't a problem. Acknowledging benefits is not the same as acting on the belief. That requires individuals to "create habits of mind," says Silverman, which is an acquired skill, she adds. It's done by continually asking, "Is there a more sustainable way to do this?" That discipline helps ECHO's staff avoid business-as-usual decisions, consistently working toward ever-greener decisions and behaviors.

At the California Academy of Sciences, the decision to go green was rooted in the convergence of three factors: Serious damage to its Golden Gate Park building caused by the Lomo Prieta earthquake in 1989; Kociolek's appointment as director; and the institution's own soul-searching and community pulse-taking. Staff, board, and stakeholders explored such questions as, What is the function of a natural history museum in the 21st century? What should it look like? What should it do? Together, board and staff explored and chose the intent for the new museum's intellectual approach and organizational programming. They then compared their conclusions to what the existing spaces in the damaged building offered, or might offer. When the existing physical plant did not support the new organizational vision, they found themselves on a new path - creating a building, a sustainable one, from scratch.

Maud Ayson's board at the Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts, came to its green epiphany through an institutional planning process as well. Fruitlands is a museum of the New England landscape that uses the site's woods and wetlands, its collections of art, Native American and Shaker artifacts, and its buildings to tell the story of how human beings have shaped, and been shaped by, the Massachusetts countryside. Appropriately, it began its green efforts by focusing on its landscape and the surrounding environment as it developed a master plan for the rural site. In 2002, the museum conducted a grant-funded public dimension assessment, MAP III, through a program of the Institute of Museum and Library Services. After interviewing staff, neighbors, and other stakeholders, the board realized it wanted the community to be as proud of the museum as it was. It then held a board retreat featuring presentations by staff and an architect from the Doyle Conservation Center, headquarters for the Trustees of Reservations ("The Trustees") in Leominster, Massachusetts, who explained why the center chose to build a LEED Gold-certified building. With the knowledge that the founder of Fruitlands was committed to protecting the local landscape and its history, what they learned that weekend convinced the board that the institution should pursue environmental sustainability.

The decision to go green was "about building community together and doing what's right for the 21st century," says Ayson. "If we're not an advocate" for smart growth, she adds, then "development could happen here." Ayson says Fruitlands staff is firmly committed to the idea that green is right for the mission and the right thing to do, and is learning to appreciate the relevance of a green approach in their daily work and lives. Ayson considers it the museum's job to protect greenspace as the best "frame" for the Native American sites and mid-19th century utopian settlement that share a landscape with the museum. And her board and staff agree: At the moment, they're working with community and preservation leaders to minimize the impact of a pharmaceutical plant scheduled to be built in open space within visual range of the property.

Precisely because many people do not have the green habits of mind that Silverman prizes and institutions do not always have the lofty expectations that each of the museums in this article has developed, it's critical to have someone on staff who can drive a green agenda. The Kresge Foundation, a leading proponent of sustainable design in the not-for-profit sector, requires every organization that applies for green project funding to demonstrate that "a 'green champion' has been designated - a person who has appropriate authority within the nonprofit organization to shepherd the integrated design process from project conception to completion." Moreover, that person's efforts on behalf of the project must be a core component of his or her work - not just an add-on to an already overfull schedule - and he or she must continue in that role after the building is complete. Silverman totally agrees, and adds that someone needs to be a green champion for planning, building, and behaving. At ECHO that person is Silverman, who calls herself the "recycle police." But with ECHO up and running, she notes that each staff member has taken on the role of champion for his or her portion of its operations and programming.

The boards and staff at these three institutions discovered the importance of sustainability early in a bricks-and-mortar planning process and only later recognized its natural alignment with responsible museum practices, which in turn caused them to change their habits. Green is all about changing behavior, Silverman says, and that isn't always easy. "If it were," she notes, "people would have changed their habits years ago." Whether it's buying recycled products, using local vendors, or researching your options for sustainable sources, being green requires mindful choices. Fortunately, as Silverman points out, with technological innovation driving green building techniques forward at an accelerating rate, it has become much easier to make the right choices.

Being green for a museum is not just about smart buildings, sustainable product choices, or environmentally aware practices. It's about commitment to the future at the board and staff level. It's about communicating that commitment to external as well as internal audiences. And, for each and every one of us, it's about how we choose to live our lives.

Excerpts from the Greening Your Museum series in the Philanthropy News Digest, posted April 25, 2007.

Sarah S. Brophy, LEED-AP, is consultant for museums, historic sites, zoos and gardens pursuing environmental sustainability in their buildings, operations and programming. She also teaches The Green Museum at The George Washington University Museum Studies Graduate Program. Currently she is a co-chair of the American Association of Museum's Professional Interest Committee on Environmental Sustainability. Sarah is the co-author of The Green Museum: A Primer on Environmental Sustainability, and author of Is Your Museum Grant-Ready? Sarah Brophy runs bMuse a consultancy for museums that believes that the defining feature of museums is experiential learning - the pleasure, power and opportunity of it. Her work focuses on helping museums become sustainable through strategic grants development, cost-saving green buildings and behavior, and in mainstreaming actions that strengthen relevance and responsiveness to the audiences they serve. Sarah will be teaching a new course for museumclasses.org MS265: The Green Museum: Introduction to Environmental Sustainability in Museums. Brophy earned her master's degree in American history from the College of William & Mary, Virginia, and a Certificate in History Administration from the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

|

Why use a Microclimate?

by Jerry Shiner

Maintaining a collection forever is not what drives designers, architects, and most of the museum heirarcy. It's not that they don't care about the survival or well being of the artifacts; it's just not the foremost thing in their mind. Usually, their own survival, and the wellbeing of their firm or institution is what is driving them. However, there are some excellent reasons that you can use to sell your colleagues on the microclimate approach. Here are some reasons to care:

Freedom

Designers, architects and their associates and clients, are severely limited by using whole building HVAC. The HVAC system takes up around 20 percent of a building's volume, and limits room sizes, ceiling heights, and much more. Using a microclimate approach allows great freedom for an architect or designer to put what they want, where they want.

This freedom extends further than just placing an artifact near the entrance for effect, or an architect providing soaring spaces. It also means that older buildings, which might never be brought up to the best modern standards of climate control (for example, ASHRAE AA, A, or even B levels) can exhibit or store materials complying with the most stringent demands for humidity and temperature control.

| | These enclosures create microclimates that surround artefacts on display |

Operating Cost Reductions Due to Smaller Volumes

It's obvious: Maintaining appropriate conditions in a small enclosure will be less expensive than supplying the same conditions in a much larger gallery or storage room. Consider the size of a typical gallery, it may have a volume of 15,000 cubic feet / 500 cubic meters. Chances are that the total volume of the display cases in the gallery is less than 1000 cubic feet / 30 cubic meters, or even substantially less. What's more, the cases are in an already isolated environment (nested microclimates), and little control may be needed.

A smaller volume will cost less to maintain, but there is a lot more to say about how and why HVAC costs are reduced when relying on microclimate environmental control.

Cost Reductions Due to Lack of People

People have a tendency to exhale moist air, not to mention their nasty habits of shedding all sorts of "dust," perspiring, and touching things. Each visitor can be seen as a load on the HVAC system - needing cooling and dehumidification power. A building's climate control system must have the capacity to remove this heat and humidity, and the capacity is still there, even when the building is empty. This is not an inexpensive proposition. The more accurate conditions you wish to maintain, the more expensive your capital costs, and operating costs, too.

But wait, there's more. When we breathe, we release CO2. This must be removed from the building and replaced with fresh air. What about all the energy we just invested to heat and humidify the air? No worries, we can retrieve much of the heat (or cold) with (expensive) machinery. The problem here is saving the energy used to humidify or dehumidify the air being exhausted.

It takes a lot of heat to boil or condense water (a phase change) - much more energy than it takes to raise or lower temperature. Therefore, the costs of humidifying and dehumidifying the air are much greater than the costs of heating or cooling the air. This expensive energy is blown out the exhaust with the CO2.

We see that operating costs rise dramatically with the need to adjust relative humidity levels, and will rise even higher as people come through the galleries and fresh air is filtered, heated, and humidified for their benefit. Needless to say, microclimate enclosures are not crowd-friendly, and need a much simpler air supply system.

A recent graduate thesis examined the costs to provide climate control for various levels of museum. In his conclusions, the author noted that for each halving of environmental control limits (say from +/- 10 percent RH to +/- 5 percent RH), there is a doubling in energy/operating costs. Costs increase exponentially. Operating costs of over $8 per each square foot of space were reported by the most tightly controlled museum. Consider that a space of 100,000 square feet of fully conditioned space is not unusual (the Metropolitan Museum in New York is over 2,000,000 square feet). A quick calculation gives 100,000 square feet multiplied by $8 per square foot = $800,000 per year in energy costs. Imagine what could be done with the money found by halving the costs, and halving them again, all the time maintaining a comfortable environment for visitors. And this is every year, and at current energy costs.

Cost Reductions Due to Capital Savings

Clearly, the cost of more powerful, bigger, and more precisely controlled HVAC equipment will add to original building costs. Maintenance and replacement costs will also be increased. All equipment is expected to break down eventually, and will have to be replaced at regular intervals.

Again, this is the tip of the iceberg. A building holds a microclimate, but unlike a simple showcase, storage cabinet, or cardboard box, a building has to withstand winds, snow, rain, sunlight, and more. As well, it has to maintain a substantial temperature and humidity differential between exterior and interior. The lesser the difference, the easier (and less expensive) the building will be to build and maintain. Sealing a building and preparing it to withstand arctic blasts while maintaining a steady 70 F / 21C and 50 percent RH is challenging.

Not all museum projects involve new architecture; many (or most?) involve renovation of existing buildings. In many cases it is exorbitantly expensive, or impossible, to convert a heritage building to withstand the rigors of differential environments.

Green Buildings

We see that a microclimate approach to environmental control can save a lot of energy, which translates easily into money. Let's not forget that energy can also translate into greenhouse gas production. A microclimate approach to storing and displaying artifacts means that buildings can be made "greener" with more passive climate controls and simpler HVAC systems.

And Don't Forget

Your time is money too. Would you rather be cleaning objects of dust shed by your visitors, repairing damaged artifacts from improper display or storage, explaining (once again) to your building engineer the problem with humidity fluctuations, or do you have something better to do?

Excerpt from MS 242: Museum Microclimates.

Jerry Shiner teaches MS 242: Museum Microclimates. He has extensive expertise in active and passive methods of mitigating and controlling humidity, temperature, pollution, and oxygen levels for display and storage enclosures. He works with architects, engineers, and conservators to design local and central systems. As founder of Keepsafe Microclimate Systems he has provided hundreds of active and passive solutions for low oxygen treatment and storage (anoxia), and showcase humidity and temperature control to museums in the US and Europe.

|

|

Northern States Conservation Center (NSCC) provides training, collection care, preservation and conservation treatment services. NSCC offers online museum studies classes at www.museumclasses.org in Collections Management & Care, Museum Administration & Management, Exhibit Practices and Museum Facilities Management.

Sincerely,

Helen Alten, DirectorBrad Bredehoft, Sales and Technology Manager

|

|

|

|

|