Workshops

taught by Helen Alten

West Virginia University workshop in Moundsville, West Virginia

Museum Materials and Boxmaking

Friday May 13, 2011

9 AM - 5 PM Contact the Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex or the Cockayne House in West Virginia for registration information. Space is limited.

American Institute for Conservation Annual Conference in Philadelphia, Penn. Museum Mannequins Tuesday May 31

10 AM - 5 PM; $139 The workshop is open to all museum staff, even those who are not American Institute for Conservation (AIC) members. A one-day registration rate of $100 will be assessed to non-conference partiipants.

|

|

Matting and Framing Microclimates

by Susan Duhl

Matting and framing provides both protective and aesthetic contributions to works on paper, paintings, and textiles. By the middle of the 19th century, it was recognized that pollution from burning coal was harming the leather bindings and paintings in London's libraries and museums. By 1850, the National Gallery in London was glazing paintings to protect them from airborne pollutants. One of the earliest references to a sealed enclosure especially designed to create a microclimate environment is an 1892 patent for a sealed case used to protect a painting by JMW Turner in 1893. [Jerry Shiner, Trends In Microclimate Control of Museums, 2007]

Frames protect their contents by creating a barrier between the work of art or artifact and the environment in which it is exhibited or stored. A microclimate is created inside the frame, which can either improve or damage a sensitive collection material. Good quality materials, such as rag mat boards, appropriate hinging, and ultraviolet filtering glazing significantly contribute to the long-term preservation of art and artifacts. Poor quality framing materials will adversely affect both the physical safety and chemical nature of the work on paper. Acids in low quality mats and wood backing materials will both leach acids and emit gasses that will deteriorate and discolor the frame's contents.

Mats, made with acid-free materials (such as rag board) physically support the art or artifact. Buffered mat boards have an alkaline content that will help neutralize naturally occurring acids in deteriorating or poor quality papers - this slows the rate of acidic deterioration. Alkaline boards should not be used with blueprints, photographs, and some other print mediums, because they will introduce negative factors in the microclimate, resulting in changes to the appearance and stability of these media.

Separating the art or artifact from the frame glazing with window mats and spacers placed inside of frame rabbets, protects sensitive paper from unwanted condensation and from physical damages like expansion and distortion of paper, in increased relative humidity. Conservation quality attachment into mats, using Japanese paper hinges and photo-corners, protect sensitive paper items from problems that result from expansion and contraction in changes of climate.

Ultraviolet filtering glazing, using products, such as Museum Glass or OP-3 Acrylic sheets, protects frame contents from harmful light exposure. Acrylic glazing can also protect the art from impact. Light exposure at any level is potentially damaging; sensitive paper-based works should have limited display time.

The closed environment of a frame can also protect the contents from moisture, which will move from humidity outside of the frame towards a drier interior. Moist interiors will likely result in expansion and distortion of works on paper, and possibly mold outbreaks. Sealing the back of the frame, or the package of matted work, backboard, and glazing, can improve the stability of the frame enclosure from moisture. Separating the frame from the exhibition wall with a gap large enough to allow airflow can further protect the frame's interior microclimate.

Microclimates are created inside any sized contained area, including folders and boxes used in paper storage, exhibition vitrines, gallery rooms, and in the pyramids of Egypt.

Excerpt from MS 233: Matting and Framing

Susan Duhl is an Art Conservator in private practice specializing in art on paper and archival collections. She is a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC) and founding member of the Art Conservators Alliance.

|

|

|

|

Welcome to the Collections Caretaker e-Newsletter from Northern States Conservation Center. This issue is devoted to the environment that affects museums and collections. The newsletter is designed to bring you timely and helpful content that is pertinent to situations we all encounter in our museum and archives work. Feel free to let us know what topics you would like to see featured in Collections Caretaker or even contribute an article.

|

|

|

5% off two or more courses

|

|

What Made Lucy Rot?

by Ernest Conrad

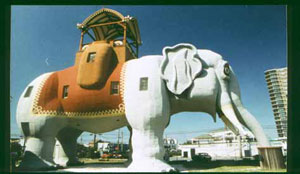

Lucy's story is a perfect example of the misapplication of insulation and its box-in-a-box climate control solution. Lucy's construction mishap created the world's largest terrarium -- and that caused rot.

| | Lucy became the world's largest terrarium. |

Who is this Lucy character? Lucy is a 65 foot tall pachyderm. Lucy the Margate Elephant was built in 1881 by James Lafferty as an architectural "folly" to promote a real estate venture. Lafferty took prospective buyers up inside Lucy through stairs in her legs. They would look out through Lucy's "Howdah," an observation deck 65 feet up in the air, to view the various lots that were for sale. At one point, a family actually lived inside Lucy. Today, she is the last of three elephants built for the project. She is an historic landmark operating as a museum on the beach in Margate, New Jersey.

How is Lucy a terrarium? Terrariums are containers designed to trap water and Lucy's construction consists of a tightly soldered tin cover wrapped over wood, supported by internal wood trusses. Lucy underwent restoration in 1976 and again in 1984. Among other things, foil faced batting was added to the wood sheathing to improve thermal efficiency. Turns out that was a bad idea for Lucy.

Lucy is a massive wooden structure, covered with a tight tin skin, located 50 feet from the Atlantic Ocean. When wood is heated it gives off moisture and when wood cools, it absorbs moisture from the surrounding air. In a cool, moist environment, wood can absorb up to 15 percent of its weight in water vapor. The next day when the sun is well up in the sky, it heats up Lucy's tin skin and all that wood sheathing underneath. The same wood sheathing that had spent last night absorbing moisture. And so the moisture in the wood gets driven out and into the batt insulation. Since there is air conditioning running inside Lucy for people comfort, the insulation is also cooled. As a result, all that moisture condenses inside the insulation and as the cycle repeats daily, moisture accumulates in the insulation pressed against the wood and causes dry rot.

How can we balance the needs of the museum and people inside with the need to keep Lucy dry? Understand that balance is not a compromise. In a compromise, both parties lose since neither gets what it really wants.

The solution is a box-in-a-box. Years ago Lucy had interior walls. Replacing them and adding a ceiling creates a large enclosed space inside Lucy -- essentially a box -- completely isolated from the perimeter envelope. Insulate the interior box walls and introduce climate control inside the interior box, which is where there are people and museum collections. In the cavity space between the interior box walls and the outside box (the elephant's legs and trunk and ears and tusks and tail, and so forth) ventilate to keep it dry. Force slightly heated outside air in one end and out the other to ensure a dry condition. And take all that insulation off of Lucy's skin. It would never dry out otherwise. This is what balance is all about. Everyone is a winner when balance is achieved.

Lesson learned: This problem will be present in any temperate climate, not just near the ocean. Many historic wood frame buildings have been compromised by well meaning people installing insulation on the underside of the wood roofing in an attic space. Think of Lucy! Put the insulation on the attic floor and ventilate the attic to the outside to keep it dry.

The box-in-a-box concept can be used almost anywhere. It is simple, reversible, and cost efficient. It only conditions the air space that needs conditioning. Many house museums can use this principle for their collections storage needs. And, it works

Ernest Conrad is a mechanical engineer with a bachelor's degree in civil engineering and a master's degree in environmental engineering from Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. For over 20 years, Mr. Conrad has focused on environmental issues. He developed environmental guidelines for engineers who work on museums, libraries and archives, rewriting the standards of the engineering field as it relates to collection holding facilities. This ground-breaking work contributed enormously to improved preservation environments in all collecting institutions. He is president of Landmark Facilities Group, Inc., an engineering firm specializing in environmental systems for museums, libraries, archives and historic facilities. Mr. Conrad teaches MS 211: Preservation Environments.

|

|

Humidistatic Heating

by Ernest Conrad

| | Humidistat |

Humidistatic heating is based on the hypothesis that humidity control is more important than temperature control when it comes to collections preservation. So it uses a humidistat to operate the heating system instead of a thermostat. The theory is simple: Just swap your thermostat for a humidistat. But there are rules you must follow for it to work.

How does it work?

If the psychrometric chart is examined around its mid range, one will note that for each change in temperature of one degree Fahrenheit (ºF), the relative humidity (RH) will change 2 percent, so long as no water is added or taken away. Pretty neat. Thus a person could change the relative humidity in a room simply by raising or lowering the temperature.

A few examples

If I am up north in the winter and it is 10 degrees Fahrenheit (-12 degrees Celsius) outdoors, and 70 degrees (21 Celsius) with 20 percent relative humidity indoors, if I lower my thermostat to 60, then the room's relative humidity will rise to 40 percent all by itself without adding moisture. If I continue to lower the thermostat to 50, then the room relative humidity will rise further to become 60 percent all by itself. So by maintaining the room between 50 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 15.5 degrees Celsius), a reasonable relative humidity of between 40 percent and 60 percent can be maintained. Not bad, so long as you don't have to live in there. But maybe this is a collections storage room where temperature is not a concern.

In another example, if I get gutsy and lower that thermostat down to 40 (4 Celsius), then the room relative humidity will rise to 80 percent, right into mold territory. It is important to understand that too cold is not a good thing. For this reason, a good rule of thumb for basements is to never let them go below 50 (10 Celsius) in the winter. This will also help prevent walls from sweating in the springtime when the weather warms outside.

The rules

What are the rules I need to know for humidistatic heating?

Rule # 1. You need a dry basement. Any active source of moisture into the building, especially a wet basement, will defeat humidistatic heating. Standing water or wet materials will try to evaporate their moisture when heated and thus the more heat is added, the more evaporation occurs and the heating just keeps spiraling up and the humidity never will go down.

Rule# 2. This is a winter thing. Humidistatic heating is a technique that is intended for climate regions where winter weather goes below freezing. It is not intended for summer use. However, in damp springtime rainy weather, it will do wonders to just bump up the heat 5 ºF as a means to ward off mold.

Rule # 3. Not for occupancy (because the temperatures get too cold). Humidistatic heating is an approach largely conceived for house museums in colder regions. These buildings are usually closed down in winter and need a cost efficient preservation program. The good news is that humidistatic heating can reduce energy costs.

Rule #4. Not for precision climate control. This is for reasonable climate control in buildings that do not have good thermal envelopes and their energy budgets are a major concern. Outdoor weather will at times not yield the desired results indoors.

Rule# 5. Computerized control is costly. Although the theory is simple, any automated controls to accomplish humidistatic heating get complex. The "human" computer may be a better choice at times. Just set the thermostat at 60 ºF (15.5 ºC) in November and lower it to 50ºF (10 ºC) in January and back up to 60 ºF in March. There is no accurate humidistat that works on normal heating system control voltages. Generally computerized controls with electronic RH transmitters are needed.

Ernest Conrad is a mechanical engineer with over 20 years experience working with museums, libraries and archives. Mr. Conrad has focused on environmental issues in these facilities, developing environmental guidelines for engineers who work on museums, libraries and archives, rewriting the standards of the engineering field as it relates to collection holding facilities. He recently coauthored the ASHRAE Applications Handbook Chapter 20; Museums, Libraries and Archives design.

|

|

Establishing a Tribal Museum

New online course sponsored by the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (NATHPO)

Course dates: May 31 to June 25, 2011

Establishing a Tribal museum - or even just expanding or enhancing one - can be daunting. It's a job that demands a clear community vision and an organized approach, which make a tremendous difference for the museum's future. Establishing a Tribal Museum will provide the facts and comprehensive advice you need to undertake this endeavor. This includes considering how your tribe's museum can get the community and financial support it needs. The course walks students through specific steps and considerations to clarify the process of establishing and maintaining a successful Tribal museum. These steps include writing a mission statement, understanding community expectations, and establishing a collections policy. Students will explore the potential role of the museum within their Native community and key considerations when establishing a tribal museum. Topics include collections care, community expectations and benefit, registration, the role of traditional culture and language within the museum setting, exhibitions, conservation, staffing and financial management. Course instructors Stacey Halfmoon and Claudia Nicholson are familiar with the challenges and pitfalls involved in establishing a new museum. Ms. Halfmoon is the director of Community Outreach and Public Programs for the American Indian Cultural Center and Museum in Oklahoma City, OK. Ms. Nicholson is executive director of the North Star Museum of Boy Scouting and Girl Scouting in North St. Paul, MN. This course is for members of US tribes who meet NATHPO qualifications. For more information, course details and to sign up go to www.nathpo.org. This online course is part of the National Native Museum Training Program funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services. |

Northern States Conservation Center (NSCC) provides training, collection care, preservation and conservation treatment services. NSCC offers online museum studies classes

at www.museumclasses.org in Collections Management & Care, Museum Administration & Management, Exhibit Practices and Museum Facilities Management.

Sincerely, Helen Alten, Director

Brad Bredehoft, Sales and Technology Manager

|

|

|

|

|